Thursday, July 30th, 2020

Thursday, July 30th, 2020

Tomorrow begins at dusk, when mourning disturbs deep summer, annually, yet again.

I, unlike Joshua of Nun, will not slow the advance of darkness, nor halt the terrestrial spin.

Sunset, when through, brings wormwood and grief, for the good of today will fade into night.

History foretold, of great blessing or curses, their glory or chains, their triumph or fright.

As it sets, mourning must begin — not yet the dawn, but sad lamentation, grief, mourning.

Be not surprised to hear of choices made long ago, or the One who gave repeated warning.

Apostrophe here interrupts Doomsday — with no apparent reason and without explanation.

Acrostics appear in their scriptures, beginning Psalms of praise, prayer, and meditation.

Valuable insights await those who decipher the Doomsdays recurrent through generations.

Tuesday, July 28th, 2020

Why this and not that?

For those who would follow Thomas Jefferson’s lead and take an editorial scissors to the Bible, I have a simple and straightforward question: Why? What is your motivating rationale? Why are you prepared and willing to cross out or cut out this particular passage and not that?

In the curious case of Thomas Jefferson, presidential scissors-hands, his motivating rationale for cutting up the four gospels is easy enough to discern, in historical retrospect. Jefferson held a philosophical commitment to strict naturalism. Like his Deist contemporaries, Jefferson rejected the possibility of anything miraculous. Jefferson was convinced that God just does not do miracles. God does not intervene, but allows Nature to run its course, believed Jefferson. In his estimation, aside perhaps from the initial creation, miracles cannot occur and do not occur, ever. Therefore, any miracle account found in the Bible must be rejected as mere superstition and fable. But lest society fall into godless chaos, Jefferson wanted to retain the high moral ideals taught in the Bible, so he deemed it best to let biblical moral teaching stand. Jefferson’s Jesus was therefore a teacher of high morality, whose idealism led him to a tragic death.

Anyone who sets out to edit, omit, or ignore passages in the Bible necessarily has a motiving rationale. Some Bible editors will clearly (and sometimes even angrily) state why they are intent on omitting or rejecting a portion of scripture. Other Bible editors will be slow to show their hand, but will instead go about their work quietly. Although I think it is easy to see, I should state that Bible editing is not just confined to academic settings. It also occurs routinely within churches. Pastors, preachers, and ministers often serve as deliberate Bible editors. They do so by simply neglecting to bring particularly problematic passages up in public.

To be fair to preachers, ecclesiastical Bible editing is not necessarily a nefarious undertaking. Sometimes it happens rather innocently. Pastor-editors may be motivated by simple confusion or uncertainty. They don’t know what to make of the passages they overlook or avoid, so they wisely steer clear. But ignorance or uncertainty cannot forever excuse a lack of attention or preparedness. A lot of the passages that initially seem problematic and confusing can be deciphered and explained with diligent study. Preachers thus need to apportion enough time to scriptural study and sermon preparation. That is much easier said than done, though, because ministry is a constant juggling act of apportioning one’s time, attention, and effort. Pray that people in ministry are wise in their use of time. Pray also that they get adequate rest.

Finally, to divulge an ecclesiastical semi-secret, political considerations usually stand behind decisions to publicly edit or silence portions of the Bible. Yes, I do mean national politics; but I also mean denominational and congregational politics. To last in ministry, a church leader must be at least somewhat socially savvy. Excessive candor will usually result in an invitation to go serve elsewhere. Smart leaders thus quickly learn the fine art of self-censorship, otherwise more charitably known as discretion. It is a skill entirely necessary for ministerial survival. But it also means that things can and do go unsaid that perhaps should be said. Disagreeable, guilt-inducing portions of scripture get neglected, because the congregants are just not ready (and may never, ever be ready) to hear the hard message. And so it goes. But every once in a while, a preacher will muster the courage to bring the relevant portions of the Bible to light and deliver the hard message. For the preacher, that is a fearsome thing, indeed. Pray that they have the courage to do so when the occasion requires.

Monday, July 27th, 2020

One of my blog-cast listeners recently sent me a text message asking if I would do a post on the authority of scripture. I said I would. When readers or listeners make requests of me, I try to comply — if I can do so without straying too far from my general eschatological/end-times focus.

For me, the tricky part of this assignment will be brevity. I intend to say as much as possible in as few words as feasible. Sigh: Do wish me all the best in this endeavor. A lot of very hefty books have been written about Biblical authority. If anyone wants to do some serious research and desires a recommendation or two, let me know. I got books to throw your way, figuratively.

As I write this, a reference book sits ready and within my reach. It is entitled The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, and was edited by a conservative theologian/professor named D. A. Carson. It is almost 1,200 pages long. But for those who want a quick and brief synopsis, Carson includes a final ~20 page chapter addressing Frequently Asked Questions. That final chapter covers a lot of relevant historical material and is well worth paging through.

The authority of the Bible has been ferociously challenged for over two hundred years now. In most of academia, the Bible is no longer taken seriously as a source of reliable, authoritative truth. Science now holds that exalted position, even though science itself is constantly in flux. Like so many of the specimens it explains, science, with a capitol S, is said to be by its nature changing or evolving; and we are taught to just roll with its inexorable evolution. Whichever turns it takes, Science itself remains unassailably authoritative. Science should always be regarded as indubitably correct, unless it corrects itself, of course. Then the latest science overturns the former. And that is because science is a self-correcting enterprise; and yet, in general, its progress is steady and sure. You can trust Science, because science establishes itself. And that is not a tautology. It is simply self-evident. Hip, hip hooray, Science!

Am I off track? Wasn’t I supposed to talk about the alleged authority of the Bible and not the indisputable authority of Science? Silly me. Sorry about the digression. Back I go to the Bible.

The questionable (or at least, constantly challenged) authority of the Bible whirls and whistles about as perhaps the most distressing issue for the contemporary Church. A lot of churches and even whole denominations are willing to overlook and even dispense with controversial and embarrassing sections of Scripture. They want to focus on portions of the Bible that are agreeable and ignore the sections that are disagreeable. In doing so, they either knowingly or (more likely) unknowingly imitate the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson.

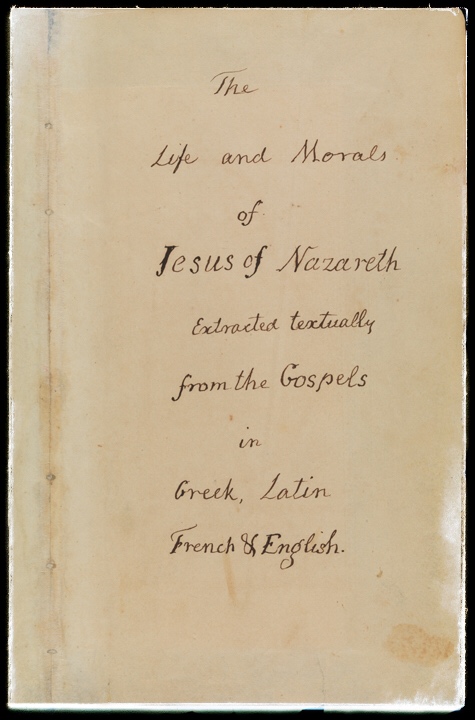

Aside from the moral matter of how he treated his African-origin slaves, which is perhaps irrelevant to this discussion anyway, Jefferson once literally cut up the four gospels in order to eliminate those passages that did not fit his preferred anti-supernatural re-reading of scripture. Jefferson even compiled his deliberate extractions into a Smithsonian-held work entitled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. But to avoid ruffling too many feathers, Jefferson did not allow this book to be published until after he died. According to Jefferson, yes, Jesus existed, but he was just a pious moral teacher who did no miracles and did not rise again from the dead. The sections of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John that say otherwise need to be seen as fanciful inclusions by the inventive, proselytizing Gospel writers. Jefferson took it upon himself to helpfully excise the supernatural fluff, and left us the likely historical material.

Relatedly, but nearly two hundred years later, the fine and learned folks associated with the Jesus Seminar of the 1980s and 1990s undertook Jefferson’s same basic project of cutting away the churchy Christian mythology of the Gospel accounts from the (scientifically ascertained) actual history of the life of the obscure Jesus of Nazareth. So you might say that Thomas Jefferson was academically way ahead of his time, at least in terms of Biblical criticism and extraction. So welcome home to a new century, Mr. Jefferson; you did not miss much.

A willingness to extract what is worthwhile in the Bible from what is fanciful or false in the Bible is premised on the assumption that at least portions of the Bible are indeed fanciful or false. A lot of people, and even a lot of “woke” Christians, wholly accept that premise today. They do believe that some sections of the Bible should be deemed either fanciful or false, or both. This is a very attractive position for people who dislike what the Apostle Paul writes. Furthermore, I will tell you that we spent significant time in seminary learning about various said sections of scripture. To my seminary’s credit, most (but not all) of my professors were intent on establishing our confidence in Scripture, not undermining it. Not every professor and not every seminary does that, though. Even in Christian schools and seminaries, a real battle for the Bible is ongoing.

In my estimation, when it comes down to brass tacks, the real issue is not as much what someone believes about the Bible itself as what they believe about God himself. I believe the Bible is reliable and authoritative because I believe that the God described by the Bible was and still is capable of delivering on his promises and relaying and keeping his word. Admittedly, I first got this idea from the Bible. More accurately, I first got this idea from the Church, which first got this idea from the Bible, through which this idea was transmitted by a cohort of earnest early Christians back in the first century. So, basically I’m saying that I’m willing to believe what the first disciples of Jesus said about Jesus. It really all comes down to just that. Everything else that matters depends on just that. With regard to the authority of the Bible, ultimately everything hinges on the person of Jesus.

Do you believe that the first disciples of Jesus reliably relayed what Jesus said and did? I do, therefore I believe the Bible. I know: That sounds massively simplistic, I realize as much and acknowledge as much. But when all the arguments and all the books are distilled down to their essence, the basic issue is the reliability of the first and nearest witnesses to Jesus. I deem them sufficiently honest, and historically reliable, and their multiple portrayals as worthy of acceptance. Do you? If so, the Bible is what we have received as our authoritative written resource. If not, Science in all its latest and greatest wisdom beckons.

Friday, July 24th, 2020

Just like English, Biblical Greek has one word that means to come, and another that means to arrive. For the Greek geeks, the words are respectively ἔρχομαι and ἥκω. But although the two words are technically different, they are commonly and casually used interchangeably. Such overlap usage is both understandable and forgivable, because we do exactly the same thing in English. Yes, we do.

For example, if she were running later than expected, I might text my wife and ask her, “When will you come home?” But if I were instead to ask, “When will you arrive home?” I would mean essentially the same thing. In such a scenario, I am basically using the words come and arrive interchangeably. No big deal; most everyone talks this way.

But if you think about it, there is technically an itty-bitty difference between the two words. To come home implies and involves the movement, transit, or (in her case) the drive from one starting point to another destination. Alternatively, to arrive specifies not the transit, but the exact ending point of the transit. Someone can only arrive after they have come.

Therefore, if my wife wanted to mess with me, she could reply to my inquisitive text with something like, “I will come home in about 15 minutes. But I will not arrive home for about 30 minutes.” In which case, I would smirk, because I would realize that she is being unnecessarily technical, when I just wanted a general answer. Plus, she knows me well enough (and English well enough) to correctly interpret my text. I just wanted to know what time she’ll get home.

But so what? I just spent four paragraphs discussing the difference between the words come and arrive. Why bother discussing the technicalities of common words?

Well, I bother because Jesus is coming quickly, but no one knows exactly when he will finally arrive. He is coming quickly but arriving slowly. Let me nuance that statement now. On occasion and all along, Jesus has been coming quickly since he ascended to heaven; but he has yet to finally and ultimately arrive.

Huh?

Jesus has not arrived yet, in an ultimate second-coming sense. That said, I should affirm that he could arrive very soon. Indeed and frankly, I expect his ultimate arrival, his Parousia, in the near future. I even hope to skip the grave and live to see it.

Alternatively, Jesus has come and continues to come (quickly) through the years. In some manner or another Jesus has already come, even numerous times. For example, Jesus came when he appeared to Saul on the road to Damascus. And Jesus came when he appeared to John on the Island of Patmos.

Someone will likely protest, “But those appearances do not count! Jesus did not actually come to Earth. Those were only visions or voices.”

Okay, I will grant you that Paul and John may not necessarily have had a physical encounter with Jesus, though in the case of John, that is entirely debatable. But they both really, truly encountered him. Or rather, Jesus encountered each of them. In that way, Jesus did actually come. They had a genuine encounter with the risen, ascended Jesus. And each of them were alive and breathing on Planet Earth when it occurred. Since he appeared to them, it is fair to say that Jesus did come for them.

Please notice that I am making a distinction here between coming and arriving. I am not saying that Jesus has arrived. I am just saying that he briefly came. In the Book of Revelation, this is an important distinction that will help a reader make sense of a lot of Jesus’ statements.

I would like to suggest that we should recognize the paradoxical validity of both the distinction and the overlap. To arrive and to come can effectively mean the same thing. But they do not always mean the same thing. In the Book of Revelation when we hear Jesus saying, “I am coming quickly,” we should ask ourselves whether he is possibly pointing to brief provisional historical appearances or to his ultimate eschatological arrival. Consider that paradoxical possibility as you read through the Book of Revelation. It might help you make sense of a number of passages. It does make sense of things for me.

Monday, July 13th, 2020

Sometimes you have to choose between two options; but sometimes you don’t.

When presented with a choice between this or that, sometimes you should ask yourself if instead you can choose both this and that.

Too often, when we are presented with a choice of this or that, we just unquestioningly accept that we have no alternative but to make a left-or-right choice, as presented. In technical language, a this-or-that choice between one option or another is called a binary decision.

Over thirty years ago, a professor of mine casually warned me, “Beware the philosopher’s dilemma.” In just four words, he taught me an invaluable lifelong lesson. He wanted me to realize that some dilemmas — some choices — need not be binary, even if reputed experts present them that way. Not every this-or-that proposition needs to be accepted as it stands. Sometimes you can and you should ask yourself, “Must I really choose between these two alternatives? Is it possible to have or to accept both?”

In summary then, wisdom obtains in recognizing when a binary choice must be made, and when not. Be wise: Choose only when you must, but refuse to choose when you need not. For the sake of brevity, I will refer to this henceforth as the to-choose-or-not-to-choose question.

This to-choose-or-not-to-choose question poses itself regularly when we read prophecy in scripture. For example, sometimes when we read a prophecy, we find ourselves wondering, “Is this prophecy going to be fulfilled literally or figuratively?” And thus you face a seemingly clear this-or-that dilemma. At such a point, you should give careful consideration to how the prophecy might be fulfilled literally. Alternatively, you should also give careful consideration to how the prophecy might be fulfilled figuratively. And finally, you should give consideration to whether the prophecy could be fulfilled both figuratively and literally, because sometimes it can and is.

This interpretive process is all much easier said than done. Our biases often keep us from thinking through all the options thoroughly. We often interpret a passage with a determination to find what we are hoping to find. We want the prophecy in question to fit a particular model or perspective to which we have already committed ourselves. It is really hard for us to make an interpretive paradigm shift, especially when we have always thought a particular way, and are an established part of a tradition that thinks the same.

And in a way, that is not all bad. We should be rather reluctant to jettison a long-established interpretation of scripture. But we should not refuse to consider any scriptural evidence that contradicts or alters our preconceptions. Attested, re-attested, and establish-able capital-T truth ought to prevail in our reading and our thinking, simply because God, by virtue of being the source and the goal of created reality, stands always and forever on the side of the truth. Indeed, how could he not? Jesus declared that he himself is the way, the truth, and the life. Ultimately, that must mean that a determined devotion to discerning the truth is the very same thing as a commitment to finding Christ and standing with God. Even venerable ecclesiastical traditions should not keep us from siding with the truth to be found in the Bible or creation.

Consequently, whenever we read prophecy, we need to ask a lot of questions of the passage, and consider a number of interpretive options. We need to respect and listen to the voices of those interpreters who have gone before us and those who stand alongside of us. After all, many of them were and are sincerely trying to hear what the Spirit says to the churches, just like us. But at the same time, we need to be somewhat open to contrarian interpretations, if only because the prophets themselves were often contrarian voices speaking from the ecclesiastical periphery. The establishment is sometimes wrong, thus saith the prophets.

But to my earlier point, to-choose-or-not-to-choose is a question we must always consider as we read through prophecy. Often we are told we must choose to interpret a passage either literally or figuratively. And sometimes that is indeed true. You have no alternative; it must be this or that. But other times, a prophecy could possibly be fulfilled both figuratively and literally. In such cases, beware the philosopher’s dilemma, and refuse to choose. Ezekiel 37 serves as a prime example of this. Please see my previous post on that passage, entitled Limit Two Refills.

Wednesday, July 8th, 2020

At least three other people have shared my first and last name. To my knowledge, one other person has shared my first, middle, and last name. His name was identical to mine. He died within the last fifteen years. He was a resident of the same state, and lived not far away. The fact that he has died and that I am still alive could potentially bring me trouble. In fact, it may have already caused some trouble, as I recently had to take documentary pains to establish my identity with state officials. On that occasion, I had to submit official paperwork to prove that I am who I claim to be, lest perhaps I be an imposter, attempting to steal a dead man’s identity.

Although I have not needed to have this conversation face-to-face yet, I imagine the day may come when I need to explain in person that I share my name with a deceased person. I may need to say something like this: “Yes, I am actually who I claim to be. Yes, that’s my legal name and has always been my name. Yes, I’m still alive, as you can see. The other guy who happened to have my same name is no longer alive. He’s dead. He died some time ago. He was not me. Same name, but different guy. He’s dead; I’m not. And I have the means to prove that I am who I say I am.”

The reason I say all this is because people and even whole communities share the same name in the Bible. Consequently, the reader has to keep straight who is who. It isn’t always easy to do. There are two or three Zechariahs in the Bible. There are two or three Joshuas. There are two or three Marys. There are two Sauls. There are two James. There are two or three Johns.

Usually, the individuals who share the same name are helpfully separated by big stretches of time, which makes it easier to keep things straight. The two Sauls are separated by well over a thousand years; and the latter Saul did everyone a favor by assuming the Græco-Roman name Paul, thereby erasing any confusion. But that is not always true. The three Marys are pretty close to each other in time and place. There is Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Mary, the sister of Lazarus and Martha, and Mary Magdalene. All of the Marys were closely associated with Jesus. If we had photos of the three Marys, it would be easier. But alas, no photos back then. Someday in glory, it will be easier.

And then there are cities. Caesarea serves as a prime example. There is more than one Caesarea mentioned in the New Testament. One sits right on the Mediterranean Sea. It is therefore known as Caesarea Maritime. An extremely important New Testament event happened there (see Acts 10, where the Holy Spirit dramatically fell upon a believing Gentile household). The other Caesarea does not sit on the sea, but near a spring in the northern highlands of Israel. It is known as Caesarea Philippi. A crucially important New Testament conversation happened there (see Matthew 16:13-20, where Jesus candidly affirms Peter’s claim that Jesus is the promised Messiah). If you’ve traveled to Israel (which I have not, yet) and visited either or both locations, the two Caesareas should be easy enough to keep separate, since one is a beach-front Mediterranean resort; and the other is definitely not. But if you’re just reading through the gospel accounts, the two cities are not easy to distinguish.

Making matters even more complicated, sometimes one biblical name is deliberately used two ways. Israel is both an individual man (also known as Jacob) and a nation. Ephraim is both an individual man and a region. Judah is both an individual man and a nation. Context usually makes it clear whether you’re reading about a person or an entire nation. But not always. Sometimes biblical writers even deliberately play on the eponymous ambiguity. When such situations present themselves, biblical readers may need to slow down, re-read, cross-reference, and even take some notes. Again, context usually clarifies matters, eventually.

Now, we must turn our faces toward Jerusalem. When they appear in prophecy, the names Zion and Jerusalem are effectively synonymous; and they are conceptually hard to keep straight. You may want to repeat that statement aloud about fifteen times, because it is an extremely important point to grasp.

In prophetic literature, the names Zion and Jerusalem are conceptually hard to keep straight.

In prophetic literature, the names Zion and Jerusalem are conceptually hard to keep straight.

In prophetic literature, the names Zion and Jerusalem are conceptually hard to keep straight.

Keep going…

Just be very aware that should you encounter the names Zion or Jerusalem in a prophecy you may be on slippery interpretive ground. In the Bible, Jerusalem is usually what you might guess — that is, a geographically-defined, map-able ancient city. But not always. Sometimes in prophecy, Jerusalem is used as a metaphorical reference or a spiritual designation. Therefore, as a prophecy reader you have to ask yourself exactly which particular Jerusalem or Zion you have before you. Here are some of your interpretive options:

Since these various Jerusalems play such an important and recurring part in both Old Testament and New Testament prophecies, careful Bible readers cannot escape these interpretive decisions. Which Jerusalem or Zion is this? You have to ask the question, time and again.

When I read the Bible and encounter the name Jerusalem or Zion, I generally start by asking myself if the passage I am reading is prophecy. If the answer is no, then it is almost always safe to assume that it is the literal geographical city or the populace thereof. But if the answer is yes, this is indeed a prophecy, then it matters greatly if I am reading from the Old Testament or New Testament. In general, the Old Testament thinks of Jerusalem in either literal, immediate, and usually negative terms or in futuristic, utopian, and positive terms. In the Old Testament, there is the corrupt, sinful Jerusalem that existed back then; and there is the purified, holy Jerusalem that is to come. But to think of Jerusalem as the entire elect people of God, including even redeemed Gentiles from outside Israel — well, wait… what? That idea is mostly foreign to the Old Testament and a rather surprising mystery, a mystery that is only hinted at here and there, a tiny bit.

In New Testament prophecy, though, that once seemingly foreign mystery comes to forefront. In the New Testament, Jerusalem/Zion is very often a symbol of the entire elect people of God, including Jewish believers and redeemed Gentiles. More simply stated, in much of New Testament prophecy, Jerusalem is one and the same as the Church Universal and Everlasting throughout all of human history. You can repeat that statement to yourself a bunch of times, too.

An extremely important thing to keep in mind is that in the end all the various Jerusalems will merge into just one holy community anyway. The Church Universal and Everlasting in heaven will someday descend down to Earth and be established here as a permanent city, both spiritually and literally/physically. That is because what is now distinct spiritually and literally will someday be fused together. In the end, there will be just one Jerusalem where God will dwell with the redeemed.

For further reading, I would suggest Isaiah 62 and Revelation 21.

Tuesday, July 7th, 2020

Monday, July 6th, 2020

When did this occur? Or is it ongoing? Or will it occur in the future?

Sometime soon, I intend to speak about this passage.