Eventually, I am going to get to my one theological point. But I am going to take a circuitous route to get there. I am going to discuss three seemingly unrelated, apparently un-theological yet academic, nerdy notions before I braid the strands together into one thoroughly theological point. Please stay with me, dear reader. I want to suggest it will be worth it. Eventually you will see how all three strands interrelate.

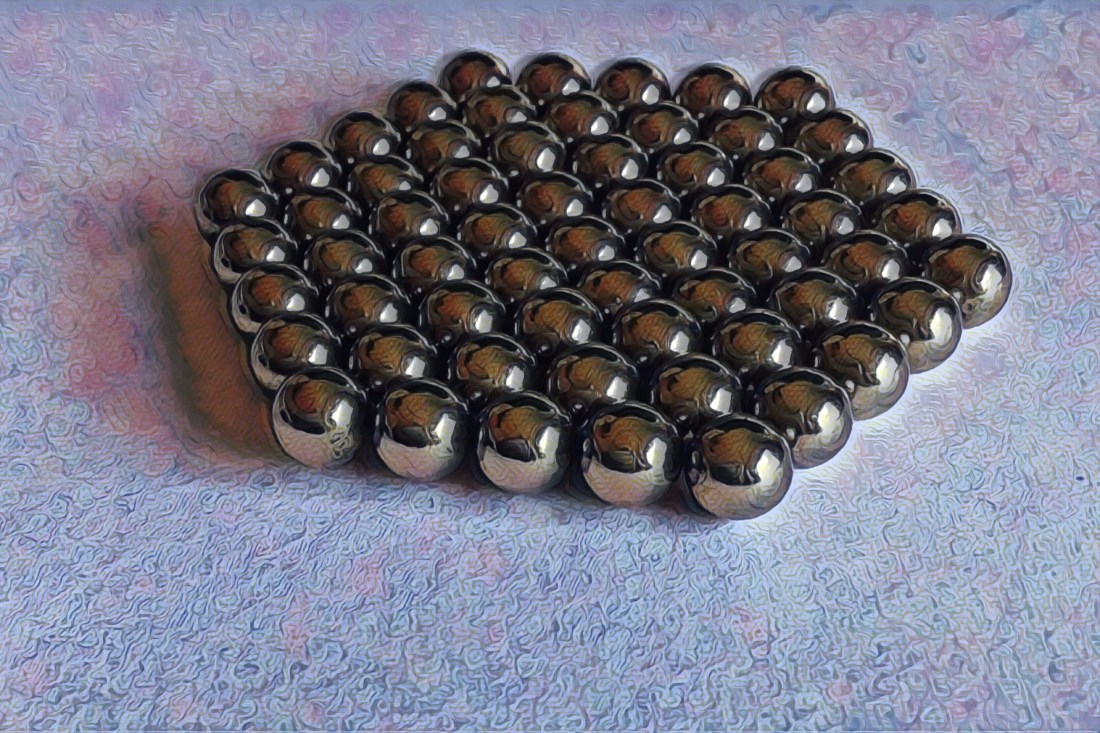

To start, let’s get mathematical. I want you to consider a mathematical concept, that being triangular numbers. Triangular numbers are better shown than described, so I need you to do your very best at imagining with me. Use your imagination. To start, imagine the number ten. Now, most of you — perhaps all of you — imagined ten as Arabic numerals — as a number one followed by a zero. Fine enough, but I want you to imagine ten identical coins, say pennies, in a particular order. We are going to imagine ten pennies in a particular arrangement, row by row. The bottom row, or base row, consists of four pennies — four pennies exactly — no more, no less. On top of that base row, you are going to imagine a second row of three pennies. Then on top of that second row comes a third row of two pennies. And one single penny goes at the very top. So do the arithmetic here: four plus three plus two plus one. What does it equal? Voila! It equals 10. Does anyone go back to Sesame Street at this point? I can hear the Count chuckling in my head; can’t you?

Alright, we just imagined our way through our very first triangular number; that being ten. The bottom row consisted of four imaginary pennies. That is, as a triangular number, ten has a base of four. Now, what number do we have if we have a base of five? Well, we would need to add five plus four plus three plus two plus one. If my rather rudimentary arithmetic is correct, that equals… drumroll… fifteen. Thus, fifteen would be the next number in the triangular number series. What comes next? What triangular number has a base of six? The answer is twenty-one. And so on. Hopefully, you are tracking with me, more or less. But what does this have to do with theology? It does. Hang on; stay with me.

If you are getting impatient with me, just know that it has something to do with the first eighteen verses of John’s Gospel, otherwise known as the Prologue to John. Really, it does.

Enough arithmetic. Let’s learn some poetry; shall we? I mean, I’m a bit of poet… although I don’t always know it. People say that I rhyme… at least, part of the time. Yeah, yeah, I know: Funny, funny… now hop along, mister poetic bunny.

Poetry… who needs poetry? Well, if you like music with lyrics, look in the mirror, because you do! Songs that are sung don’t work well unless they are somewhat poetic.

At the moment, the kind of poetry I want to consider is Haiku. Haiku is only properly Haiku if it follows certain set rules. Otherwise, you have bad, awkward Haiku, which is not really Haiku at all. Someone help me here, please. What are the poetic rules of Haiku? According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Haiku is “an unrhymed poetic form consisting of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables respectively.” Notice that what matters in Haiku is the number and arrangement of syllables.

Syllable? Huh? Remind me: what is a syllable?

Students… students… always remember, you need to put the em-pha-sis on the right syl-la-ble.

Huh? I’m still confused.

Okay, words sometimes consist of more than one syllable. For example, take the word example. The word example has three syllables: Egg-Zam-Pull. Moreover, oftentimes one of the syllables in a multiple-syllable word gets pronounced emphasis. For example, take the word emphasis. In the word emphasis, the emphasis goes on the first syllable, so that the “em” is spoken a bit longer and harder than the “-phasis” part of the word. Hopefully, this makes some sense. Hope-full-ee. Groan.

Anyway, you might start to wonder again what this has to do with theology. And once again, I want to point you to the Prologue to the Gospel of John, the first eighteen verses of the book. The rules of poetry and syllables might just matter when you read that particular prologue, possibly.

And finally, let’s go to science class, specifically to biology. In biology class, you will learn that an individual person inherits various physical traits from that individual’s biological parents. Your biological parents passed along some of their genes to you. No, you did not inherit your physical traits from just anybody. You inherited your physical traits from the genes of your biological parents, from your father and your mother. Please notice that the emphasis here is especially on the notion of genes, inherited traits, and genetics; okay? Okay.

With some math, a little poetry, and basic genetic biology in consideration, we can now turn to the Prologue of the Gospel of John.

As for math, first I informed you about triangular numbers. The triangular numbers that you need to know when we look at the first eighteen verses of the Gospel of John are 171, 325, and 496, which respectively have as their bases 18, 25, and 31. The triangular number 496 is especially pertinent to our ponderance, as we shall see.

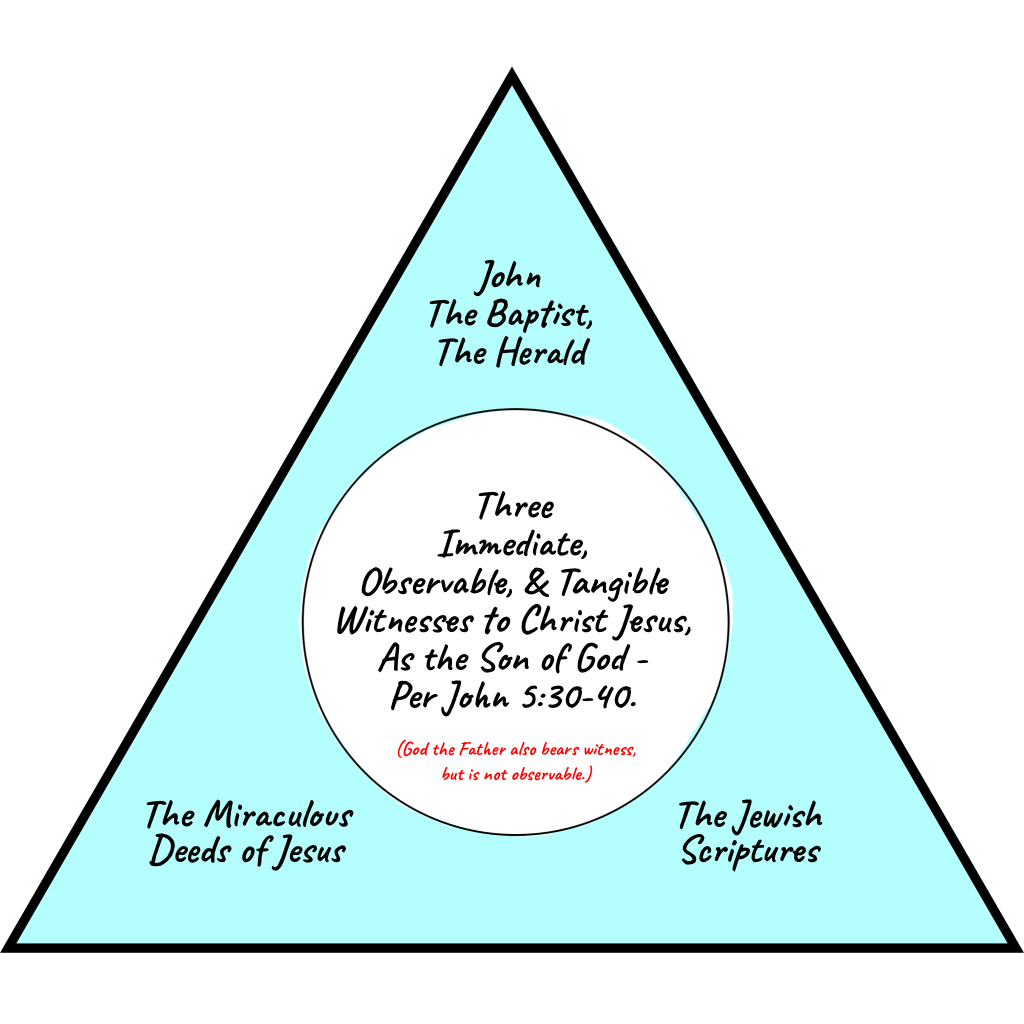

Let’s skip ahead to science for a moment, though. In our previous paragraph on biology, we learned (or were reminded) that physical inheritance is based on genetics. We inherit our physical characteristics on basis of the genes passed along by our parents. Originally, the word for gene comes another language, from ancient Greek. And, as it so happens, the Gospel of John was first written over 1,900 years ago in a variation of… drumroll… ancient Greek, a variation called Koiné Greek. In fact, the Koiné Greek word that is the basis for the word gene appears in the thirteenth verse of the Prologue to the Gospel of John. That word is γεννάω, or, more exactly, a variation thereof. It carries the connotation of parenting and inheritance. Precisely, the word γεννάω has to do with birth. In verse thirteen, the word refers to those who “were born … of God.”

Ah, so all the circuitous academic information is starting to come together. This is indeed starting to be theology.

But wait! There’s even more!

Let’s read the next verse, John 1:14. Regarding Jesus Christ, it says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt (tabernacled) among us. We observed his glory, the glory as the only begotten from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

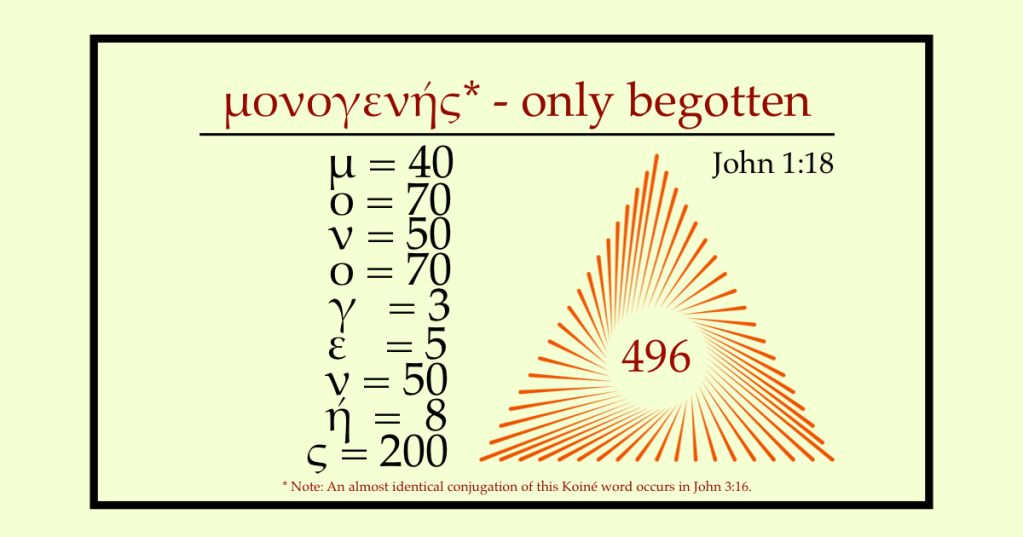

Everything discussed thus far converges right here, around just one word. Actually, in English it converges on two words; but in Koiné Greek it’s just one word. “Only begotten,” as it is rendered in ye olde King James Version English, would be the two convergent English words. In Koiné Greek, the one convergent word is μονογενοῦς (a very close variant of its lexical form, μονογενής, for anyone familiar with the original language). The word μονογενής would be transliterated as monogenās into English. Monogenās is a compound word, mono + genās, with the second half, the genās portion, meaning born or begotten. The first half, mono, means one, or only, or unique. Together the compound word means only begotten or uniquely born. Hence Jesus was the only begotten of God, or the uniquely born child of God.

To be sure, Jesus was uniquely born, given what another Gospel writer (that is, Luke), tells us about his miraculous conception.

But what about the triangular numbers mentioned previously? One of the interesting things about many ancient languages is that their letters doubled as numbers. Consequently, any word or name becomes an equation. In Koiné Greek, the word μονογενής can be added up, resulting in the sum 496. So what? Aside from the fact that 496 is a triangular number (and a perfect number — look it up), it also happens to be the number of syllables in the Prologue to the Gospel of John. Who says so? The late professor Maarten J.J. Menken says so, in his 1985 dissertation publication entitled Numerical Literary Techniques in John: The Fourth Evangelist’s Use of Numbers of Words and Syllables.

Professor Menken argues that the Prologue to the Gospel of John was carefully constructed around the word μονογενής, with the Prologue’s total syllable count (496) equaling the sum of the word itself (496). Moreover, the Prologue is structured so that the syllable sections end at three triangular numbers: 171, 325, and 496. Thus, the first eight verses have 171 syllables. The first thirteen verses have a total of 325 syllables. And the entirety of the Prologue has 496 syllables.

Similar numerical techniques are to be observed elsewhere in the New Testament, and indeed, the whole Bible, says Professor Menken, who provides a number of examples. (Yes, that does make this blog post essentially a book report… and a teaser.)

Someone may observe, “Interesting enough, but what does it really matter?” We will consider that question another time. But in anticipation of what is to come, I will say that you might-could notice that the structure of the Prologue all points to one single word, which shows you what the author himself considered to be his most important point. Also, a close cognate of the same word appears in John 3:16. The author wants you not to miss that Jesus is unique in history, insofar as he is the only begotten of God, indeed the only begotten God.

Hasta, for now. Oh… and Merry Christmas.