Here in the United States, the two words “Chapter Eleven” are usually associated with debt, insolvency, and bankruptcy. The eleventh chapter of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code provides a means of debt reorganization under court supervision. A Chapter Eleven Bankruptcy becomes an unhappy legal necessity when a corporation or an individual has debt that cannot be met. No one wants to go through the considerable trouble of a Chapter Eleven Bankruptcy. It is always best avoided. But sometimes it has to happen. Sometimes it becomes inevitable. When creditors come knocking and the bills go unpaid, a Chapter Eleven Bankruptcy sometimes becomes unavoidable and necessary. A Chapter Eleven Bankruptcy is unwelcome, unpleasant, and undesirable — except if it ends well. And every once in a while, it does end well.

Now let’s turn from Chapter Eleven of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code to Chapter Eleven of the Book of Revelation. It ought to be said up front that one major similarity exists between the two Chapter Elevens: yuckiness. They’re both rather unpleasant eventualities. Both Chapters Eleven are very, very undesirable. Like Chapter Eleven of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, Chapter Eleven of Revelation involves a lot of hardship, humiliation, and hostility. For faithful Christians, Chapter Eleven of Revelation is no fun. But it ends quite well.

Welcome to Chapter Eleven of the Book of Revelation. Welcome to an uncertain future. Expect a bumpy ride. Our immediate future will likely be a dystopian nightmare. Chapter Eleven brings us past the present day and into a dismal future.

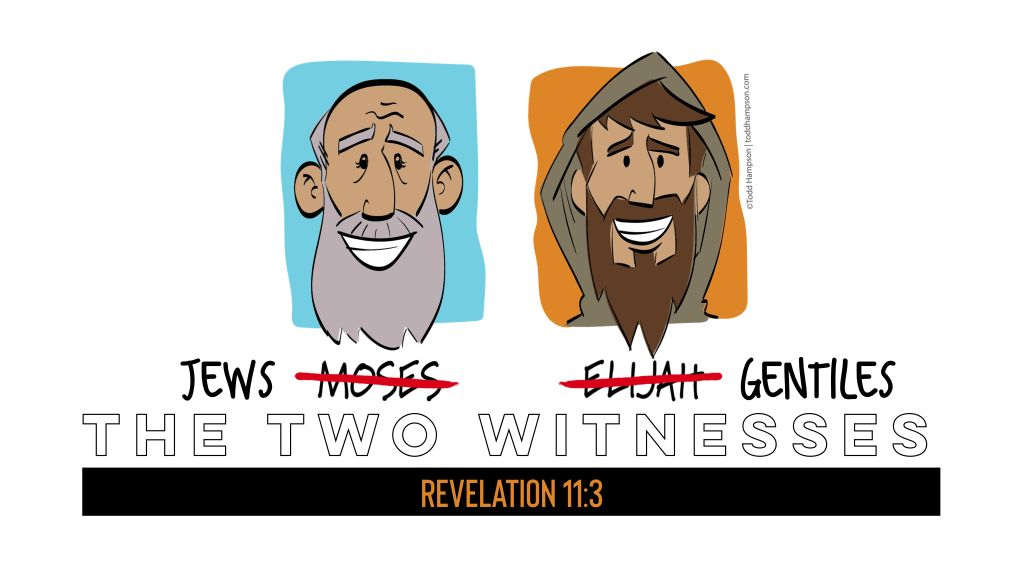

In Chapter Eleven you will read about Two Martyrs. The English translation you read will almost certainly say “two witnesses.” Your translation is not wrong; it just fails to catch the nuance of martyrdom that is there. The original Greek word is actually martyr. And in Chapter Eleven, the two witnesses are more than just witnesses. They physically die. They are killed. They are killed for their testimony. They are martyrs.

Some interpreters will say that the Two Martyrs will be Moses and Elijah. Those interpreters are slightly right and mostly wrong. The Two Martyrs will be prophets like Moses and Elijah. But Moses and Elijah will not be the Two Martyrs. The text never says they will be. Instead, the two martyrs are much more immediate. You and I will potentially be the Two Martyrs. Yes, you may be a martyr. And I may be a martyr. Reconcile yourself to that possibility right now. We are supposed to count the cost. It could well cost you your life. Jesus made that very clear when he called his disciples to take up their cross and follow him. He was serious.

I forewarned you. This is not a pleasant chapter, at least not up front.

Someone somewhere is asking how I see all this in Chapter Eleven. How do I come to these conclusions? Why do I settle upon this interpretation?

As I mentioned in my last blog-cast, Chapter Eleven presents a number of symbols from the very first verse. It mixes a lot of seemingly strange metaphors. And yet for someone familiar with the Bible, these are easily recognizable metaphors. Most of the metaphors presented in Chapter Eleven are used elsewhere in the Bible as metaphors for just one thing: the Church Universal. We are being presented with a symbolic, metaphorical collage of the Church.

In the end, when the Two Witnesses are finished with their testimony, the ascendant Beast from the Abyss will make war on them, conquer them, and kill them (see Revelation 11:7). The Beast from the Abyss will bring about their elimination. The Two Witnesses will be slain in the Public Square. Their corpse (singular) will be under close watch. Their corpses (plural) will be left unburied. Their opponents will celebrate their demise, albeit only briefly.

On one hand, this can be understood to mean that the Two Witnesses will be physically killed. On the other hand, it can be understood to mean that the Two Witnesses will be politically or economically eliminated. I mean that the Two Witnesses will be forcibly silenced or otherwise rendered incapacitated. Based on what has happened historically, I think that both types of killing will occur. Not every Christian will be physically killed, but some will. And those who are not physically killed will be incapacitated through social or economic means. The Church will be silenced, sidelined, and persecuted immediately before Christ returns. Yes, I do know in some places this is happening right now. I just think that the scale and the intensity will increase immediately before the Church is resurrected and rescued. When he taught about the events at the end of the age, Jesus instructed his disciples to pray that they have the strength to escape all these things (see Luke 21:36). It is no mistake that his words were recorded in scripture for later generations. We likewise are supposed to pray that we have the strength to escape or endure all these things.

This is the gist of the first ten verses of Chapter Eleven. This is the ugly part of the chapter. Much happier events are soon to occur. But for now, those happier events must wait.

Many interpretive questions linger. I did not cover everything in the first ten verses. I know that. I am leaving a lot of questions unanswered. I mean to answer more questions sometime soon. But I wanted to cover the essential message of the first half of Chapter Eleven first. I intend to work through more of the details in upcoming blog-casts.