Thursday, February 25, 2021

Can someone cease to be a Christian?

“Obviously yes. Next question.”

But wait a second: The answer is not an easy and obvious “yes” for someone who takes the Bible seriously.

Recently, I spoke with a friend of mine about this question, which has ceased to be merely hypothetical and become more immediate. Someone near and dear to him publicly claims to be a believing Christian, but privately fails to behave like one. In essence my friend asked, “Does hypocrisy and moral inconsistency ever disqualify someone from the Christian faith?”

The question of potential disqualification vexes Christians like my friend (and, to a degree, me). If moral inconsistency and blatant hypocrisy do disqualify someone from the Christian Faith, can anyone ever actually remain qualified? Most Christians will readily admit to a degree of inconsistency, and will acknowledge moments of shameful hypocrisy. We call it sin (or, if not, know that we should). And we are supposed to confess sin as such whenever we know we have committed it.

But can someone simply go too far? Is there a time (or are there times) when someone is no longer a genuine Christian because he or she has sinned too egregiously, or has been too inconsistent for too long? These are important issues, and can be urgent existential questions for those who take their Christian faith seriously. For now, I will restrain myself from launching into ready examples and real-life case studies. Instead, I just want to push the disqualification question to the forefront. It is a question that worries a lot of people, so it requires a good, thoughtful, biblical answer.

A closely related question is whether a genuine Christian can ever actually abandon the Faith. Can someone become an actual apostate, an ex-Christian? Sadly, on occasion, this is not hypothetical. Sometimes individuals will openly renounce once-held faith in Christ. Sometimes ex-Christians become vocal opponents of Christianity. I once met a woman who was matter-of-fact and outspoken about her status as a former Christian. She did not seem to care that her Christian relatives and friends found her claim extremely worrisome. She had been persuaded to be contrary to Christianity. She was no longer a Believer. To use once-common Christian vernacular, she has lapsed. Yet she was certain that her lapse was more than just a temporary lapse: Hers was a permanent determination and identification. She has voluntarily denied Christ. She is an apostate.

But wait a second, because as a Bible-believing Christian this is disturbing and disorienting: Even a potential lapse from sincere Christian faith seems to contradict some scriptural assurances and promises regarding the unlikelihood thereof or even its impossibility. At the very least, such a scenario does not easily square with statements that Jesus once made about his metaphorical sheep being entirely un-snatch-able (see John 10:28).

So which is it? Can someone cease to be a Christian or not? Is apostasy a real possibility?

To make things quicker and easier for my listeners, I am going to fast-forward and skip directly to my theological conclusion here in this paragraph. In classic term-paper style, I am going to state my thesis first, and then give my supporting evidence. But I hesitate. I wonder if I would actually do better to lay out the Scriptural evidence and only thereafter state my conclusion. Hesitation aside, I will argue that the preponderance of relevant Scriptural passages — including some very clear and sharp commands — insist on the continued need for diligent, vigilant, faithful perseverance. That one observation pushes me to the conclusion that it must be possible for some individuals to disobey (through unbelief and persistent sin) to the point of their own damnation. The command to persevere negatively implies that someone might actively choose not to persevere. Although I believe it is quite rare, a person can indeed lapse completely from the Christian Faith, particularly if and when that someone is wholly determined to reject Christ and walk away. Should such a determined lapse occur, it is more than a mere temporary lapse; it is a final, irreversible defection. It is apostasy. According to one especially relevant passage (Hebrews 6:4-8), the apostate defector is thereafter beyond any hope of spiritual recovery. In such a case, the breach cannot and must not be attributed to God. God was faithful to both the defector and to His promises until the final terrible breach of faith occurred. But this is an absolute worst-case scenario. I suspect that God is much more likely to bring someone to an untimely, premature death than to allow such an utterly horrifying occurrence (see 1 Corinthians 11:27-31, which speaks of Christians getting sick and dying because they do not judge themselves properly). Yet we must not claim that no one ever truly goes apostate, because Scripture does allow for it as an open possibility. Again, see Hebrews 6:4-8, in particular.

However, I need to stress that in most cases of sinful self-justification and moral inconsistency, God patiently works to bring the carnal, back-slidden Christian back to Himself. The inward-dwelling Holy Spirit, although grieved and stifled, persistently calls that person to repentance, again and again, with appeals to his or her memory and conscience. This is by far the most frequent state of spiritual affairs for those who have turned away from obedience to God. Although such a person is estranged from God by rebellion, he or she has not yet completely rejected Christ, and, given the faithful persistence of God, probably never will.

Bear in mind that God is likened to a parent throughout Scripture — especially to a loving Father. One reason why that is so is because parents have a unique bond with their children, and are especially unlikely to give up on their children, even in the worst situations. A good and loving parent will only sever the relationship with his or her rebellious child if that child is bound and determined to reject the parent, or if the rebellious child endangers the family. God is like any good and loving parent, only more so.

Now I ought to list and comment on some of the most relevant passages. I have already mentioned Hebrews 6:4-8. Anyone wishing to deny the possibility of outright spiritual defection and bona-fide apostasy needs to adequately grapple with and explain this sobering, scary passage. Most of the time, when it is explained away, it is said to be simply subjunctive, merely hypothetical — an as-if-but-not-actual thought exercise. I wonder why the Holy Spirit would see fit to include a stern Scriptural warning about something that is not really a possibility. On Jesus’ own authority, we take it as a general given that the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of Truth (see John 16:13), and thus will never warn us against disingenuous scenarios that can never actually occur. The passage is there, and is there for a reason. It is a stern warning against forsaking our faith to the point of apostasy. We should not explain it away.

Hebrews 3:12-13 comes as an earlier warning in the same book. In tone, it anticipates the extreme seriousness and severity of Hebrews 6:4-6. Indeed, it is accurate to say that the entire Book of Hebrews was written to encourage Christians to keep the Faith and not quit. I will return to Hebrews 3:12-13 at the end of this post.

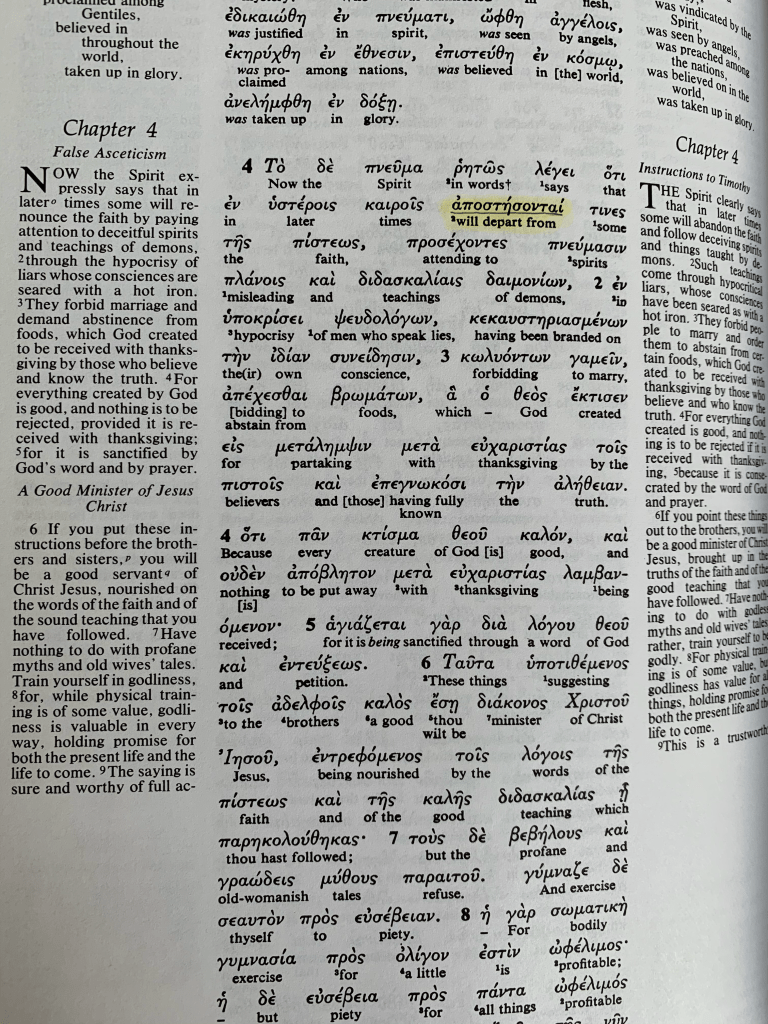

According to 1 Timothy 4:1 “the Spirit explicitly states that in latter times some will depart from the Faith by devoting themselves to deceitful spirits and teachings of demons.” Again, Jesus elsewhere identifies the Holy Spirit as the Spirit of Truth. The Spirit (of Truth) clearly states that in latter times some will depart (transliterated: apostatize) from the Faith. How does anyone argue with what the Spirit of Truth clearly states? (Yet some do, and doggedly so.)

But I should not be rash or dismissive. Why do some people say that Christians cannot actually depart from the faith? To be fair, the real reason is because they correctly say that God loves us, remains ever faithful, and is wholly determined to never let us go. They especially lean upon passages in the Gospel of John, such as John 6:37-40 and John 10:27-30. In those passages, Jesus says that he will “lose nothing” of what God gives to him, and that “no one will snatch” his sheep out of his hand. These are immensely important passages that are especially comforting to anyone prone to worry. I once heard a preacher say that if anyone does harbor the worry that “all is lost and my salvation is now void,” that same worry is a sure and certain sign that their salvation is neither lost nor void. That preacher was very likely right, because such worry probably demonstrates a righteous, God-ward desire. And God will certainly not disown any of the redeemed who do not disown Him (see Psalm 51:17).

But I need to say more about the twin “eternal security” passages in the Gospel of John. To start, there is another passage in John that points the other direction. In John 15:2, Jesus uses a gardening analogy to assert that bad, unfruitful branches get cut off, but good branches are pruned so as to produce even more fruit. It is interesting to note that Hebrews 6:7-8 uses a nearly identical analogy to warn against the real possibility of apostasy. So there’s that.

As for the fact that Jesus will “lose nothing” of what God gives him, and that “no one will snatch” his sheep out of his hand, I do admit and think it is fair to say that we might-could conclude that Jesus’ reassuring statements here teach eternal security, except for everything else against eternal security in rest of the Bible. Simply said, there are just too many New Testament passages that point the other direction. Thus we seem to have signposts pointing different directions. Sometimes we do encounter tension and paradox in Scripture. These passages are admittedly paradoxical (but not contradictory). We need to wrestle through the paradox — or just accept the tension — lest we quickly lose our balance.

And how might we lose our balance? We might lose our balance by presuming that someone’s salvation is secure no matter what they say or do, on one hand, or by fearing that some sin means that we are no longer acceptable to God, on the other hand. Salvation is not a ticket that someone can pocket, neglect, and forget. Alternatively, salvation is not a fragile snowflake that evaporates away because of a stubborn, sticky sin. Salvation is instead a security deposit that is guaranteed to be valid, if only it is valued for its worth.

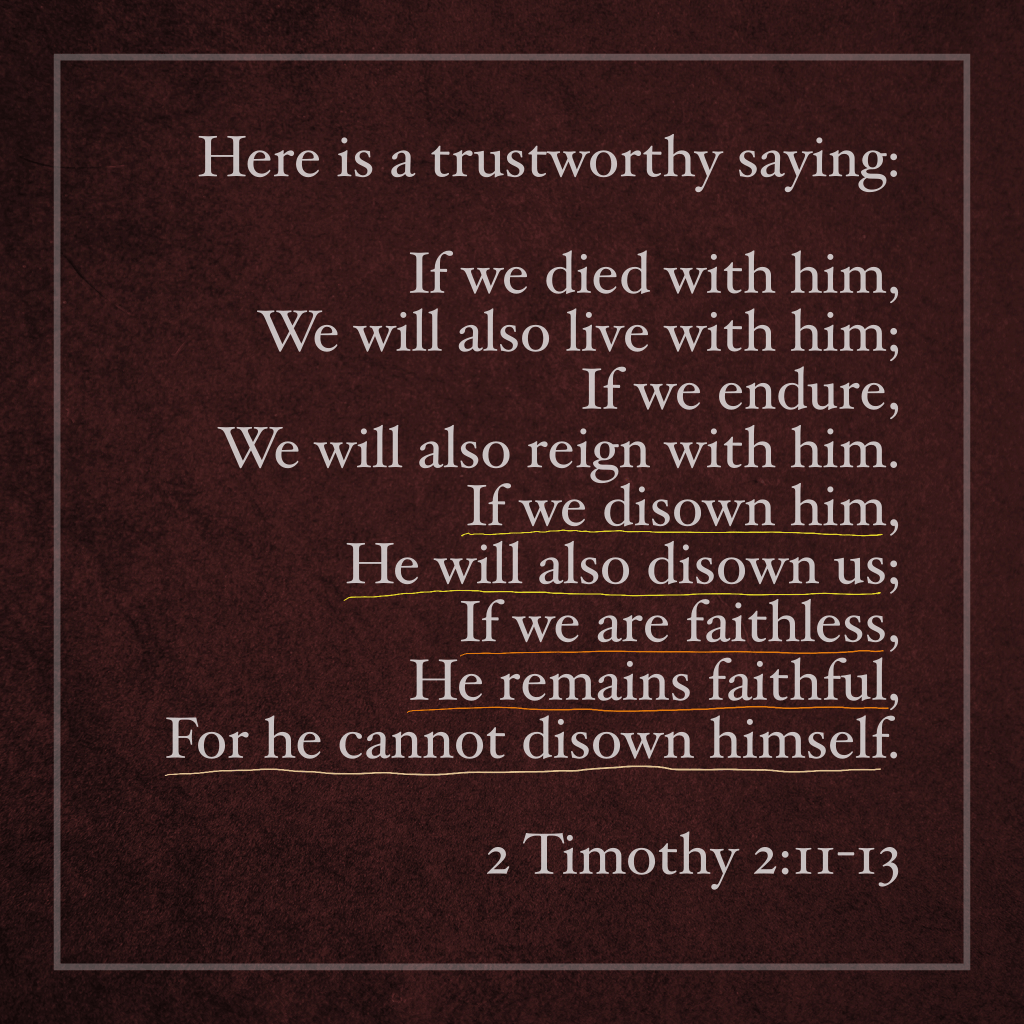

In 2 Timothy 2:11 we find this “trustworthy saying,” which (according to a scholar named Ralph P. Martin) might have been an early Christian baptismal creed or hymn:

If it was an early Christian baptismal creed, this “trustworthy saying” both warns new, initiate Christians against intentional apostasy and reassures them of Christ’s continual faithfulness. They were warned never to disown Christ, with the threat that if they did, Christ would likewise disown them. But they were reassured that Christ would remain absolutely faithful to them, even if and when they slipped into faithlessness.

My friend comes immediately to mind here. This particular passage ought to reassure him. Most of the time, faithlessness is our problem, not outright, intentional apostasy. We slip into sin because of our faithlessness. But that is not the same as deliberate “I once believed but now actively oppose Christianity” apostasy.

Finally, I want to return to Hebrews 3:12-13, which reads:

12 See to it, brothers [and sisters], that none of you has a sinful, unbelieving heart

that turns away from the living God.

13 But encourage one another daily, as long as it is called today,

lest you be hardened by the deceitfulness of sin.

Whomever Wrote Hebrews (Scholars Still Debate This)

The danger with sin is not that it immediately ends our salvation. It does not. We know from Hebrews 6 that if salvation is actually lost, it can never, ever be regained. And we know from the Gospel of John that Jesus himself is absolutely committed to keeping us from falling away. So we need not worry that sin will somehow easily strip us of salvation. God is not fickle, nor weak. And God will fight us tenaciously to keep us saved.

Instead, what we actually need to worry about is that sin will seduce us and deceive us. When we sin, we give ourselves over little-by-little to deception. And the deeper we sink into deception, the more likely we are to be hardened by sin. Someone who does apostatize has gone down exactly that path, and has gone down it a very, very long way. An apostate has first embraced sin, then fallen deeply into deception, and finally has lost all connection with the living God. Terrifying to even consider.

All that said, we cannot be completely certain that someone we meet or know is an actual apostate, even if that person claims to be an ex-Christian. God is ultimately the one who judges people; and God knows our hearts even better than we do (see 1 John 3:20). Like any good parent, God is exceedingly patient with us because He loves us deeply. If we believe someone we know may be an apostate or may be in danger of becoming an apostate, we ought to pray earnestly for that person’s return. There might still be hope for him or her, because God always desires everyone to be saved (see 1 Timothy 2:4).